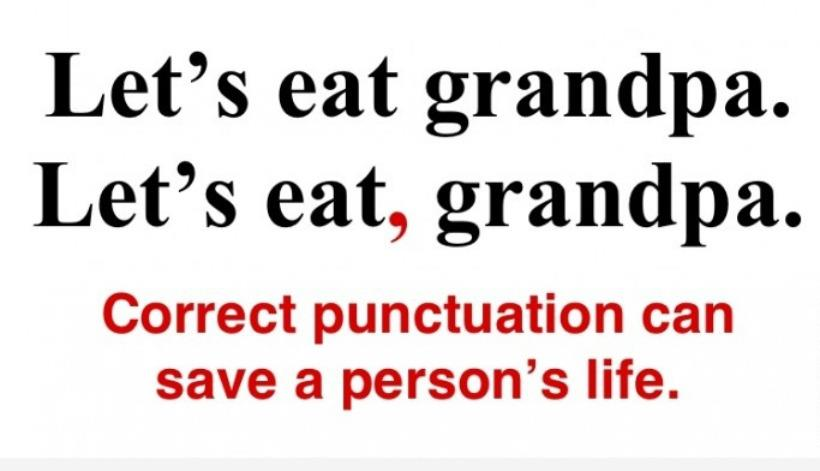

One of the most common errors I see in business writing is the misuse of commas with names and titles. If you’re trying to figure out when to use commas with someone’s job title, just use these formulas to see three correct ways to express the same information.

[Name], the [job title] of [company name], [rest of sentence].

The [job title] of [company name], [name], [rest of sentence].

[Company name] [job title] [name] [rest of sentence].

Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, plays the ukulele.

The chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett, plays the ukulele.

Berkshire Hathaway chairman Warren Buffett plays the ukulele.

Why do job titles sometimes need commas and sometimes not? It depends on whether the sentence contains restrictive or nonrestrictive elements (also called essential or nonessential elements).

The top two examples each contain a nonrestrictive clause between the two commas, meaning that it doesn’t restrict the meaning of the rest of the sentence. If you removed that clause, the sentence would still make sense.

Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, plays the ukulele.

The chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett, plays the ukulele.

Warren Buffett plays the ukulele.

The chairman of Berkshire Hathaway plays the ukulele.

As my trusty reference guide Universal Keys for Writers explains,

“Commas signal that the extra, nonessential information they set off (useful and interesting as it may be) can be removed without radically altering or limiting the meaning of the independent clause. Think of paired commas as handles that can lift the enclosed information out of the sentence without making the sentence’s meaning confusing.”

But in the bottom example, Warren Buffett is a restrictive element, meaning that it restricts the meaning of the rest of the sentence. If you removed that information, you’d be left with an incomplete sentence.

Berkshire Hathaway chairman Warren Buffett plays the ukulele.

Berkshire Hathaway chairman plays the ukulele.

Universal Keys commands, “Do not use commas to set off restrictive information.”

Next time you’re writing a sentence containing a name and job title, follow these steps to figure out if you need commas or not:

- Use the formulas at the top of this guide.

- Put commas where you think they should go, and then try removing them. If the sentence still makes sense, you need the commas. If the sentence sounds wrong, you need to leave the commas out.

- If you’re still not sure, send me an email. I will happily tell you the answer.

For more fun with commas, check out 5 Surprising Places You Need a Comma and 3 Surprising Places You Don’t Need a Comma.

Photo credit: By TheYellowFellow (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Spoiler Alert: This post contains a mild spoiler for the Netflix show Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. If you haven’t watched it yet, do, but in the meantime, scroll down and start reading the next section. It will still make sense, I promise.

Spoiler Alert: This post contains a mild spoiler for the Netflix show Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. If you haven’t watched it yet, do, but in the meantime, scroll down and start reading the next section. It will still make sense, I promise.

We’re all counting down to the upcoming three-day weekend, but many of us don’t know how to write the name of the holiday on Monday correctly. Is it Presidents Day? How about President’s Day? Presidents’ Day? Well, it all depends on whom you ask.

We’re all counting down to the upcoming three-day weekend, but many of us don’t know how to write the name of the holiday on Monday correctly. Is it Presidents Day? How about President’s Day? Presidents’ Day? Well, it all depends on whom you ask.